The Political-Reform Movement Scores Its Biggest Win Yet

Election changes such as ranked-choice voting and nonpartisan primaries are popping up across the country—and are already upending national politics.

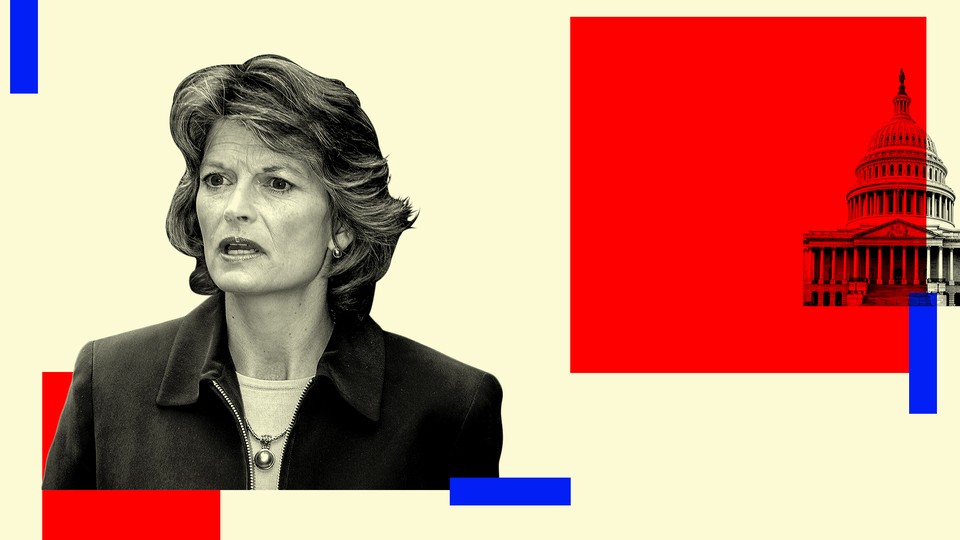

Lisa Murkowski did not waste time, and she did not mince words. Just two days after former President Donald Trump provoked an insurrectionist mob to storm the Capitol on January 6, Alaska’s senior senator told her local newspaper: “I want him to resign. I want him out.”

Murkowski was the first GOP senator to demand Trump’s exit after the deadly riot. The speed and bluntness with which she spoke out against the former president surprised her allies, who saw in her words the first reverberations of how Alaska voted in November. Murkowski wasn’t on the 2020 ballot, but in passing a ballot measure to change the way the state elects its leaders, Alaskans effectively gave their long-serving senator a fresh infusion of political freedom: She no longer needs to worry nearly so much about a conservative primary foe defeating her next year. “I think we’ve seen the result of it already,” former Alaska Governor Bill Walker told me.

The ballot measure that Alaska adopted by a narrow margin last fall represents the farthest-reaching changes to any state’s election laws in recent memory, giving a boost to political reformers who are trying to increase voter participation while reducing the incentives for partisanship across the country. Its advocates hope the reforms will be a model for other states, leading to a shift in how both Congress and state legislatures function in the years ahead. And for the next two years, they will have their eye on Murkowski.

The referendum scraps party primaries in favor of a single nonpartisan primary, a move that might help Murkowski more directly than any other politician in Alaska. In 2010, Murkowski was defeated in a Republican primary and secured her second full term only after mounting an unlikely write-in campaign in the general election. She’s up for reelection next year, and before Alaska passed its ballot measure, Murkowski was seen as once again vulnerable to a primary challenge because of her votes against her party, whether in rejecting the GOP’s attempt to repeal the Affordable Care Act or opposing Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court.

As recently as September, former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin was teasing a possible primary challenge to Murkowski. But as remarkable as Murkowski’s immediate denunciation of Trump was, equally notable was the silence among her peers that followed. Palin said nothing, and Trump loyalists made no serious move to rebuke, censure, or oust Murkowski even though they have threatened other Republicans, such as Representative Liz Cheney, who faces a primary challenge in Wyoming and an effort to remove her as chair of the House GOP conference in Washington after voting to impeach the president.

The absence of a backlash to Murkowski’s move against Trump is more evidence that the new laws have altered Alaska politics, supporters argue. The idea isn’t to push Murkowski, a lifelong Republican, to the left—she’s already ruled out switching parties—but to allow her to keep voting independently when she sees fit, whether that’s to break with Trump or to work across the aisle on areas of common ground with President Joe Biden.

Opponents of the Alaska ballot measure have sued to stop its implementation. But if it survives a legal challenge, the state will hold a nonpartisan primary for all statewide and federal offices beginning this year. The top four candidates will advance to the general election, where Alaskans will use ranked-choice voting to determine a winner. The referendum also significantly boosts disclosure requirements for campaign financing in an effort to crack down on so-called dark money pouring into state elections.

California dropped partisan primaries a decade ago, and Maine voters approved the use of ranked-choice voting in 2016, but Alaska is the first state to combine the two reforms. Alaska and Maine are separated by more than 4,000 miles, but many of their voters share a similar distaste for the two major parties. More than six in 10 voters in Alaska aren’t registered as either Republicans or Democrats, and both states regularly elect independent candidates to statewide posts. The impetus for change in Alaska somewhat mirrored the dynamics that led Maine to adopt ranked-choice voting, after the conservative firebrand Paul LePage twice won gubernatorial races without once securing a majority of the vote. In Alaska, the conservative Republican Mike Dunleavy captured the governorship in 2018 after the incumbent, Walker, a political independent, dropped his reelection bid and endorsed the Democrat Mark Begich in the final weeks of the race.

Walker’s former chief of staff, Scott Kendall, wrote the ballot measure and raised money for its campaign. He also has ties to Murkowski, having served as her lawyer when she won reelection in 2010. “Her greatest leadership moments have been her greatest weaknesses,” Kendall told me, referring to the senator’s high-profile breaks with Trump and GOP orthodoxy that made Murkowski vulnerable on the right. “I have watched as the two-party election system, the plurality system, has been trying to shake these people off. I was really kind of feeling around personally for a system that couldn’t be manipulated.”

Kendall pitched the idea around, seeking money from political organizations who could help fund a statewide campaign to pass the ballot measure. Groups aligned with both parties turned him down. “‘Tell me how it’s going to elect Democrats. Tell me how it’s going to elect Republicans,’” he recalled hearing. “To me, that was not the point.”

Ultimately, the ballot measure faced opposition from prominent members of both the GOP and the Democratic Party in Alaska. Murkowski, who declined an interview request, never took a position on the proposal. Dunleavy urged voters to reject the reforms, and one of his top aides quit his government post to launch a group to campaign against it. Begich also came out against the proposal. The opponents, Kendall told me, even included two groups who almost never see eye to eye: the Alaska affiliates of Planned Parenthood and the National Right to Life Committee. Yet the ballot measure narrowly prevailed, topping 50 percent by just a few thousand votes.

“In retrospect, I’m still kind of shocked we pulled it off,” Kendall told me. “They should have beaten us.”

The drive for election reform began organically in Alaska, but the money that pushed it over the line came from out of state. One of the effort’s biggest backers was a group called Unite America, which has ambitions that extend far beyond the Last Frontier. The organization—one of a constellation of groups trying to fix the nation’s democratic dysfunction—began in 2014 as an effort to back centrist candidates before pivoting in recent years to push systemic changes to the way Americans elect their leaders. Its benefactors include Kathryn Murdoch, a daughter-in-law of Rupert Murdoch whose philanthropic efforts to fight climate change and enact political reform diverge ideologically from the conservative ethos of the Murdoch family’s media brands. Unite America’s public face is Nick Troiano, a 31-year-old whose job is to sell men and women much older and wealthier than he is on the necessity of investing tens of millions of dollars to rewrite election laws across the country.

Troiano grew up as a Republican in rural Pennsylvania, a young politics junkie who listened to conservative talk radio and had a photo of Ronald Reagan on his bedroom wall. But he became disillusioned with the party in college, interning with a group trying to recruit a unity presidential ticket in 2008 and then working with the bipartisan Simpson-Bowles commission in 2010, tackling the national debt. “It just became so clear to me that the country is going broke because our political system is broken,” Troiano told me over Zoom recently. He finally left the GOP entirely in 2013, after Senator Ted Cruz and other hard-liners orchestrated a government shutdown over the Affordable Care Act.

Troiano is now trying to elevate “political philanthropy” from a bit player to a major force in the industry of politics, with a long-term plan to change election laws in enough states to change Congress itself. The big idea: If more lawmakers in the House and Senate are, like Murkowski, rewarded rather than punished for working together, the institution as a whole will be far more responsive to voters. Yet groups like Unite America face criticism from leaders in both parties who see their push for electoral reforms as merely a cloaked campaign for ideological centrism—for a politics that champions the mushy middle instead of clear principles of governance. They’re trying to boost people, Begich told me, “who may not have any philosophical belief on a lot of issues—people who just kind of move with the polls.”

The challenge, as Troiano sees it, is one of scale and money. Of about $14 billion in political spending during the 2020 election, just a tiny sliver—about $37 million—went to advocacy for nonpartisan ballot measures in a handful of states. After spending $3 million in 2018, Unite America mobilized more than $30 million in the past two years, and it hopes to ramp up to $100 million through 2022 and more in the years after. In addition to nonpartisan primaries and ranked-choice voting, the group is pushing states to expand voting by mail (which many already did in 2020 because of the pandemic) and to end gerrymandering. Unite America scored wins in Alaska and in Virginia, where voters approved a nonpartisan redistricting commission, but in Massachusetts, voters rejected a ballot measure to adopt ranked-choice voting. Florida came close to approving a top-two primary system; a ballot measure earned majority support but fell short of the 60 percent threshold needed to pass.

In the months since the election, Troiano and other advocates have been trying to figure out why reform succeeded in Alaska but failed in Massachusetts. One reason, he told me, was simply that Alaska voters were more dissatisfied with the political system—and their leaders—than voters in Massachusetts. In Massachusetts, Democrats largely backed ranked-choice voting, but the proposal drew opposition from Governor Charlie Baker, a popular Republican moderate. The ballot measure was perceived, Troiano said, “as a solution in search of a problem.”

But the other lesson from 2020 might be more instructive about the future prospects of political reform. Combining a series of complicated reforms into a single package proved easier to sell to voters, Troiano told me, “than when we’re only talking about one reform and having to explain the nuances of how it works.”

Critics of the Alaska ballot measure agree with Troiano, but their conclusion is a harsher one: They blamed Unite America and other advocates for using the bulk of their ads to highlight the proposal’s crackdown on dark money, a perennial source of complaint in Alaska, rather than the far more complicated, and significant, changes to how elections are run. “It was a little bit disingenuous the way they approached it,” Begich told me. He said he supported the campaign-finance piece of the ballot measure but opposed ranked-choice voting. “I’m not willing to settle for a second best or third choice. I want my first choice,” Begich said. “If I lose, I lose, then we go to the next election.”

In California, both Republicans and Democrats have complained about the top-two primary system because it results in general elections that shut out the opposing party in many areas that are deeply conservative or liberal. Expanding to four candidates in Alaska was aimed at limiting that dynamic, but critics of the proposal say that in certain parts of the state, Democrats or Republicans could still be shut out. “That limits people’s choices. That does not expand them,” Nora Morse, a Democrat who served as Begich’s campaign manager, told me. “If I’m looking at four Republicans on the ballot,” she said, “I’m going to be voting for someone who’s the least-worst candidate.”

Supporters of ranked-choice voting argue that it eliminates the spoiler effect, allowing voters to support a long-shot candidate without worrying that it will end up helping the candidate they dislike the most. But Kendall said some Democrats told him that in a conservative state like Alaska, the spoiler effect was their best chance of winning.

Others like Morse said that Alaska’s history of electing independents and the occasional Democrat like Begich negated the need for overhauling its laws. “I don’t think the system is broken,” Morse said. “In fact, we’ve had a lot of opportunity for people who don’t necessarily fall in a Democratic or Republican mindset to get on the ballot and to win.”

Begich, who served a single term in the Senate before the Republican Dan Sullivan defeated him in 2014, also faulted the national group for trying to use Alaska as its guinea pig. “We were their experiment because we’re a cheap market to get into, and a small population base,” Begich said.

That’s not a point Unite America would argue with. Troiano sees the Alaska victory as “a proof of concept” that the group can pitch to donors to stand up campaigns in other states, whether through voter-led ballot initiatives or lobbying state legislatures. Walker, the former governor, told me he hopes the Alaska model will “sweep the country.”

I asked whether the reforms that voters approved last year would have made a difference in his tenure. “Absolutely,” he replied. Walker said that he would not have governed differently—“I didn’t hold back,” he insisted—but that his proposals for closing the state’s budget gap might have drawn more support. Time and again, he recalled, members of both parties—although more Republicans than Democrats—would tell him they couldn’t back bills, because they wouldn’t “survive a primary.” “I was just irate when I heard,” Walker told me. “I said, ‘Don’t use those words in my presence or with anyone.’”

The dynamic is a familiar one in Washington, where Republican senators worried about their right flank will likely be reluctant to lend Biden any support for his agenda. The fear of a primary defeat has tamed even renowned “mavericks” like the late Senator John McCain, who tacked sharply to the right for a time after he lost the presidency to Barack Obama in 2008. Thanks to Alaska’s new election laws, however, Murkowski might not be one of them this year. If her quick and sharp call for Trump’s resignation is a guide, she feels free to break with the Republican base when she wants to. And even though Alaska hasn’t run a single election under its new system, supporters see the political liberation of its senior senator as the earliest sign of its success. “I think we can expect to see more of the same,” Kendall told me. “Now her greatest leadership moments are to be rewarded, rather than punished.”